previous years

previous years

HINESISCHE ZULIEFERER GEWINNEN AN BEDEUTUNG, ZU UNGUSTEN DER DEUTSCHEN UND JAPANER

München, 08. Juni 2022 Im Rahmen der großen Top 100-Zuliefererstudie hat Berylls Strategy Advisors die 100 weltweit größten Automobilzulieferer bereits im elften Jahr in Folge analysiert. Nicht anders als 2020, das durch den Sondereffekt Corona seinen Stempel aufgedrückt bekam, wurde auch 2021 durch die anhaltende Pandemie, durch die Chipkrise und durch die verschärfte Situation auf den Rohstoffmärkten massiv beeinflusst. Dennoch können viele Zulieferer im Geschäftsjahr 2021 wieder deutliche Umsatz- und Profitsteigerungen ausweisen. Sie nähern sich Schritt für Schritt dem Vorpandemie-Niveau an. Groß angelegte Restrukturierungsmaßnahmen tragen ihren Teil dazu bei. So liegen die Umsätze der 100 weltweit größten Automobilzulieferer im Jahr 2021 mit 899 Milliarden Euro (+13,4 Prozent gegenüber 2020) deutlich über dem Niveau des von Covid-19 geprägten Vorjahres, allerdings nur knapp zwei Prozent unter dem bis dato stärksten Jahr 2019. Auch die durchschnittliche Profitabilität kann mit 6,3 Prozent wieder deutlich gesteigert werden und liegt damit auf dem Niveau der Jahre 2018/2019. An dieser positiven Entwicklung nimmt auch die Gruppe der deutschen Zulieferer teil, allerdings weniger stark als die chinesischen Konkurrenten.

Bosch verteidigt im siebten Jahr in Folge den ersten Platz in der weltweiten Aufstellung der 100 größten Automobilzulieferer, insgesamt bewegt sich unter den Top 5 nichts. Wie im Vorjahr liegen zwei weitere deutsche Unternehmen auf den Plätzen 3 (Continental) und 4 (ZF Friedrichshafen). Magna behauptet sich auf Platz 5. Auch für die Reifenhersteller Michelin und Bridgestone lief das Jahr 2021 gut, sie behalten ihre Platzierungen und damit die Plätze 8 und 9.

2020 sorgte Weichai Power für eine echte Sensation. Denn Weichai Power war der erste chinesischer Zulieferer überhaupt, der in die Phalanx der Top 10 vordringen konnte. Das Unternehmen, entstanden aus einem Hersteller für Dieselmotoren und heute im Segment der Software für Lkw und Pkw tätig, kann sich im Topsegement aber nicht halten, rutscht in 2021 auf den immer noch sehr respektablen Platz 12 ab.

Dennoch ist mit CATL weiterhin ein chinesisches Unternehmen in den Top 10 vertreten. Der Akkuhersteller springt, mit einem Umsatzwachstum von 184 Prozent im Vergleich zum Vorjahr, erstmals in die Spitzengruppe und schreibt damit innerhalb der Top 50 eine einmalige Erfolgsgeschichte. Berylls Partner und Zuliefererexperte Alexander Timmer: „Das ein Batterieproduzent in die Top 10 aufrücken würde, ist wenig überraschend. Denn die Nachfrage nach Akkus war selbst im schwierigen Jahr 2021 so groß, dass CATL in der logischen Folge zu den ganz großen Gewinnern zählt. Ohnehin ist der chinesische Konzern ein guter Bekannter innerhalb der Top 100. Im Ranking für das Jahr 2018 lag CATL noch auf Platz 71, hat allerdings seither eine beeindruckende Entwicklung gezeigt.“

Aber Chinas Zulieferer sind nicht nur im Bereich der neuen Antriebstechnologien stark, wie das Abschneiden von Citic Dicastal belegt. Das Unternehmen, dessen Kernprodukte Leichtmetallfelgen für Pkw und Lkw sind, schoss im Top 100-Ranking um beeindruckende 26 Positionen nach oben und findet sich in der diesjährigen Übersicht auf einem starken 62. Platz. Insgesamt haben es neun chinesische Zulieferer in die Top 100 geschafft. Das Cluster der chinesischen Zulieferer kann sehr stark von der lokalen und nationalen Industriepolitik profitieren, die einerseits den chinesischen Binnenmarkt stärken soll und andererseits eine Expansion in internationale Leitmärkte befeuert.

So wächst der Beitrag der chinesischen Zulieferer an der internationalen Umsatzentwicklung stetig. Im Jahr 2018 lag er noch bei fünf Prozent, 2021 können die Chinesen bereits einen neunprozentigen Anteil für sich verbuchen. Der Zuwachs geht zu Lasten der deutschen und japanischen Zulieferer. Deutschland war am Gesamtumsatz 2018 mit stolzen 23 Prozent beteiligt, Japan steuerte 27 Prozent bei. Beide Nationen verzeichnen seither schmerzhafte Rückgänge. Die deutschen Zulieferer tragen nur noch 21 Prozent zum globalen Gesamtumsatz der Branche bei, die Japaner 24 Prozent. Schreiben die Chinesen ihre Erfolgsgeschichte konsequent fort, werden sie im Jahr 2028 die Vorreiterrolle im weltweiten Zulieferer-Ranking einnehmen und die deutsche Konkurrenz aus der Spitzengruppe verdrängen.

Im Covid-Lockdown-Jahr 2020 mussten Zulieferer und OEMs harte Umsatz- und Profitabilitätseinbrüche hinnehmen. So konnten nicht mehr als acht der in der Top 100 Übersicht gelisteten Unternehmen 2020 gegenüber 2019 überhaupt ein Umsatzwachstum aufweisen. Im vergangenen Jahr hat sich das Bild praktisch komplett gedreht. Lediglich zehn der 100 weltweit größten Zulieferer waren nicht in der Lage ihren Umsatz zu steigern. Zu diesen Low-Performern gehören: Yazaki, Panasonic, Mitsubishi Electric, GKN, Thyssen Krupp Automotive, NSK Group, NHK Spring, NGK Spark Plug und TS-Tech. Sieben von ihnen gehören zum japanischen Zulieferer-Cluster.

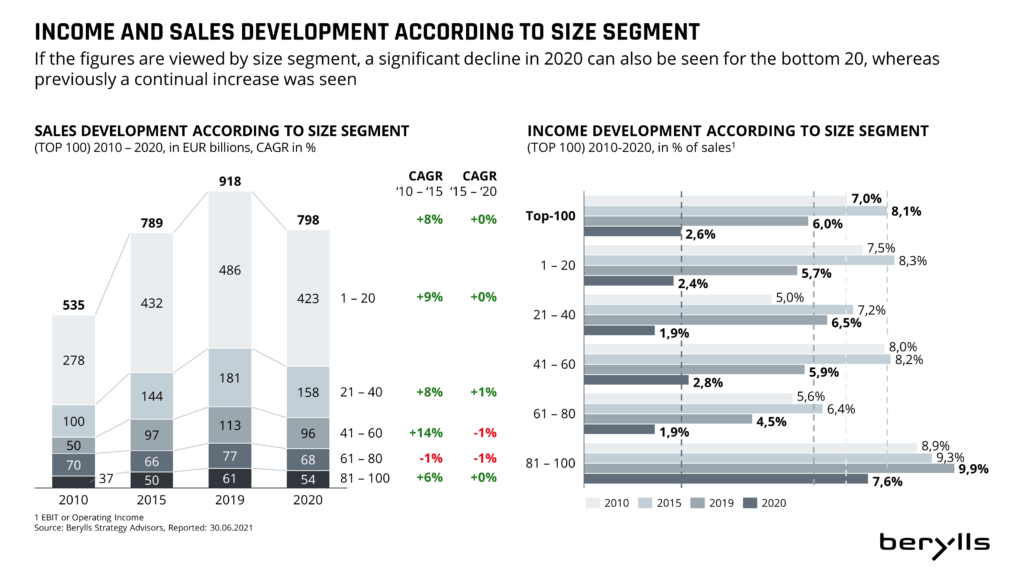

Dass 2021 ein erfolgreiches Jahr für die Branche war, zeigt sich auch darin, dass 58 Zulieferer 2021 bereits wieder höhere Umsätze als vor dem Ausbruch der Pandemie erwirtschaften. Im Vergleich zu 2020 hat sich die durchschnittliche Profitabilität von 2,6 auf 6,3 Prozent mehr als verdoppelt.

Allerdings ist der Erfolg nicht gleichermaßen auf die Branche verteilt. Er betrifft vor allem Firmen im Bereich der Halbleiterindustrie. Denn so paradox es klingen mag, an der positiven Gesamtmarkt-Entwicklung hat die Halbleiter-Knappheit einen großen Anteil. Was bei den OEMs zu einer Drosselung der Produktion und vollgeparkte Logistikflächen mit unfertigen Fahrzeugen führte, ermöglichte bei den Chip-Lieferanten 2021 Absatz-, Umsatz- und Profitrekorde. So konnten die Halbleiter-Hersteller ihre Automotive-Umsätze überproportional um durchschnittlich 34 Prozent steigern. Sie erzielten Margen von 19 Prozent, während der Top 100-Durchschnitt bei eher mageren 6,3 Prozent lag und damit sogar unter dem der OEMs, die mit ihrer Ausrichtung auf das Premiumsegment einen Zehnjahreshöchstwert von 7,4 Prozent erzielen konnten.

Mit dem Ende der weltweiten Lockdowns erholte sich die Wirtschaft rasch und entwickelte einen nie dagewesenen Hunger auf Rohstoffe. Die Preise für verschiedene Metalle und Kunststoffe erreichten deshalb 2021 Rekordhöhen und vermiesten der Industrie das Geschäft. Betroffen waren nicht nur die für die Batterie- und Elektrofahrzeug-Produktion wichtigen Metalle wie Nickel, Kobalt und Lithium. Auch die Preise gängiger Industriemetalle und Kunststoffe stiegen von 2020 auf 2021 signifikant: Kupfer +23,5 Prozent, Stahl +66,7 Prozent, Aluminium +37,8 Prozent, Magnesium +130,5 Prozent, Messing +34,3 Prozent und Polypropylen +94,4 Prozent. Die hohen Rohstoffpreise trafen die Zulieferer deswegen so hart, weil sie sie überwiegend nicht an ihre Kunden weitergeben konnten. Eine kurzfristige Änderung der Situation ist nicht zu erwarten, im Gegenteil, es ist mit einem weiteren Steigen der Preise zu rechnen, auch bedingt, durch den Krieg in der Ukraine. Das Embargo gegen Russland schneidet die Industrie von ihrem wichtigsten Lieferanten für Palladium und Nickel ab, gleichzeitig fällt die Ukraine zumindest teilweise als Lieferant für das Edelgas Neon aus, es ist ein wichtiger Bestandteil der Halbleiterproduktion.

Die E-Mobilität beschäftig die Branche mittlerweile vollumfänglich. Die Aktivitäten von Bosch in diesem Bereich beispielsweise, sollen bis zum Jahr 2025 um 500 Prozent wachsen. Aktuell gibt der weltgrößte Zulieferer an, im vergangenen Jahr in diesem Sektor eine Milliarde Euro Umsatz erwirtschaftet zu haben. ZF kann sich im Jahr 2021 ein Auftragsvolumen in Höhe von 14 Milliarden Euro sichern und baut damit seine Position bei elektrischen Komponenten weiter aus. Viele bedeutende Lieferanten für Komponenten des elektrischen Antriebsstrangs und des autonomen Fahrens kommen aus Deutschland. Neben den genannten Firmen Bosch und ZF, können auch Continental, Dräxlmaier und Leoni ihre Positionen im internationalen Vergleich verbessern und durchschnittliche Umsatzsteigerungen im zweistelligen Prozentbereich gegenüber dem Vorjahr realisieren. Dass die E-Mobilität, aber auch das autonome Fahren und die ADAS-Systeme Wachstumsmotoren sind, zeigt sich im Vergleich zum Branchendurchschnitt: Hersteller aus diesen Segmenten fahren im Durchschnitt eine zwölfprozentige Umsatzsteigerung ein. Aber der Weg zum Erfolg bleibt steinig, denn gleichzeitig fordert die Transformation hohe Entwicklungsausgaben mit mehrjährigen Amortisationsdauern. Das drückt die Profitabilität in den Anfangsjahren mit geringen Produktionsvolumina; sie liegt 2021 bei unterdurchschnittlichen sechs Prozent.

previous years

or automotive suppliers, the year 2020 was exceptional. The scale of the disruption can be summarized in four statements: growth was only really possible through acquisitions; one in four companies recorded losses; a Chinese supplier made it into the Top 100 for the first time, and electromobility set the direction for the whole industry.

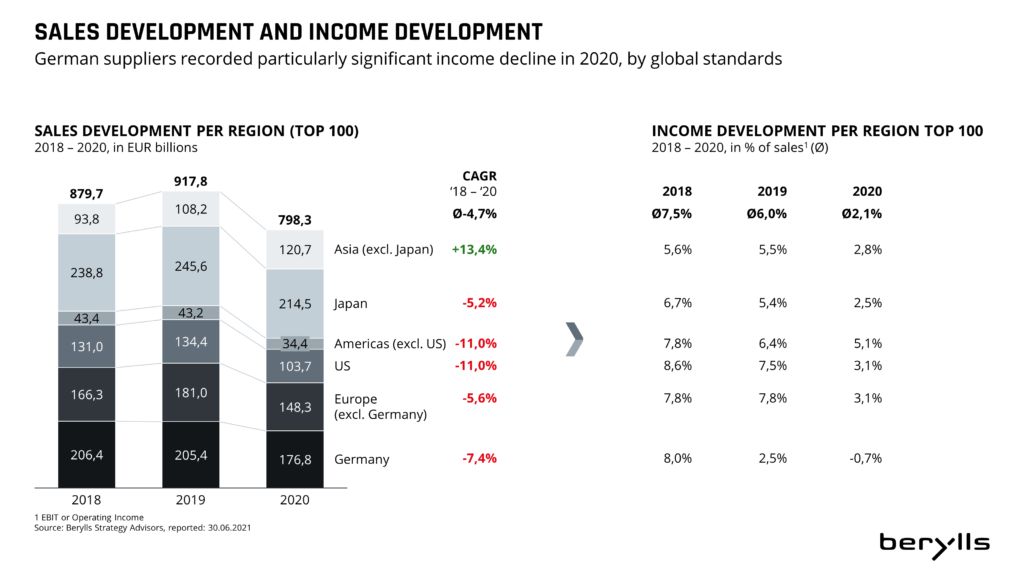

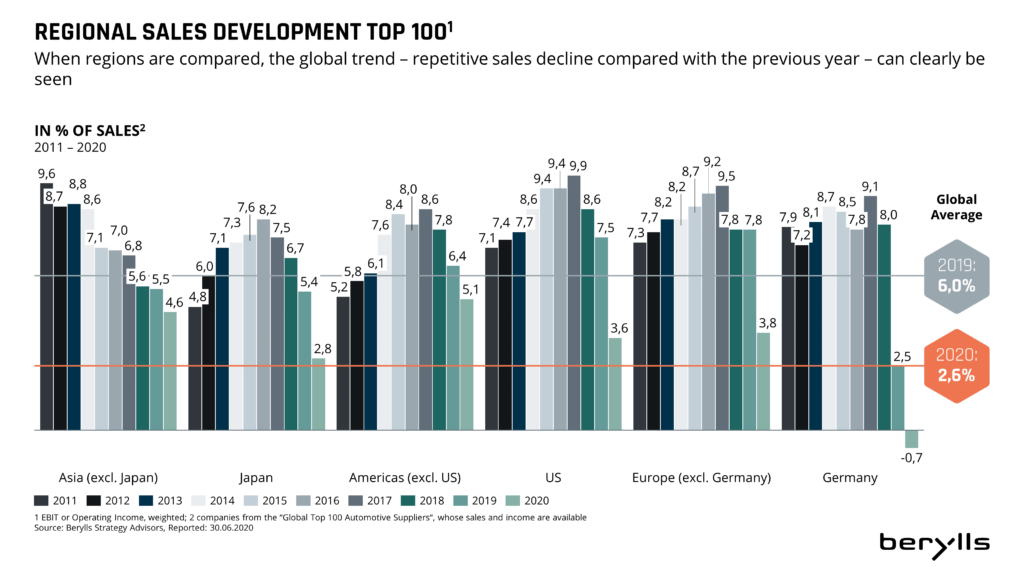

Looking in more detail at the numbers, turnover among the 100 largest automotive suppliers as identified by Berylls Strategy Advisors was 12.7 per cent down compared with 2019, when turnover increased by 4.3 per cent. Profitability among the top 100 declined by 58.1 per cent in 2020 in comparison with the previous year, and the average margin of the companies surveyed stood at 2.6 per cent less in 2020 – less than a half of the 6 per cent achieved in 2019.

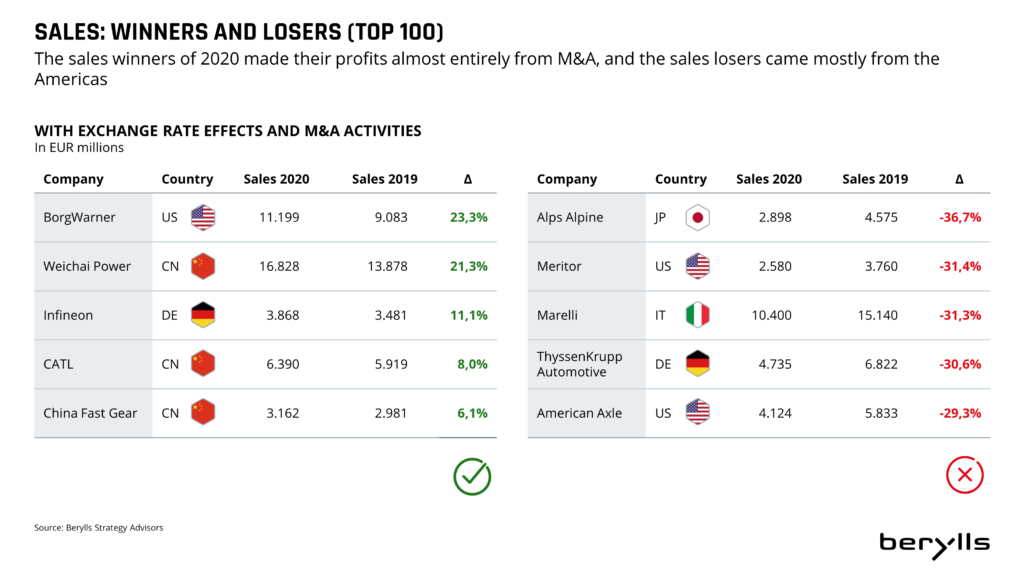

After a stormy year, for which the omens were already clear in 2019, the analysis by Berylls shows that whereas normally ten companies with the strongest growth in turnover could be selected, this time there were only eight. That was the number achieving a greater turnover than in the previous year. The 9th and 10th places in 2020 went to the two suppliers showing the least reduction in turnover in the Top 100. The main reasons for this are the effects of the Coronavirus pandemic. In the course of the past year both OEMs and suppliers had production stoppages. These stoppages along with reduced demand were the cause of significant loss of sales for the companies. It was mainly through acquisitions that companies such as BorgWarner (Delphi Technologies), Weichai Power (Aradex, VDS) or Infineon (Cypress) succeeded in increasing sales into a respectable double figure range.

There were mergers throughout the year. For example, Hitachi Automotive Systems, Keihin Corporation, Showa Corporation and Nissin Kogyo merged with the Japanese “Top 20” supplier (planned turnover for 2021 of 13 billion euros) Hitachi Astemo.

It was mainly the Coronavirus pandemic and the resulting production stoppages which caused sales drops for the automotive suppliers industry in the past year. Every second German supplier is currently planning additional job reductions because of the effects of the crisis. To add to this, sales fell considerably and costs did not fall to the same extent. One prominent example for the problems caused by the pandemic is the German cable and wiring specialist Leoni, which had already got into difficulties beforehand and is included in the 2020 Top 100 companies even with a negative margin. 80 factories belonging to this supplier all over the world were closed at various times, and the majority of its 4,800 staff in Germany were on short-time work. Rescue came in the form of a guarantee issued by Bavaria, Niedersachsen and Nordrhein-Westfalen for an operating loan. This prevented the company from going bankrupt, and it promises improvements in sales and results for the current year. Some smaller German suppliers which are not included in the Top 100 had to tread the path to insolvency in 2020, such as rim manufacturer BBS, the battery factory Moll, the aluminium casting experts Finoba, the plastic components manufacturer Weberit Dräbing, and the die-cast components manufacturer Minda KTSN. Some have already been taken over by investors or at least have the prospect of a restructuring. So the wave of bankruptcies announced in the previous year’s report has well and truly arrived. However, unlike the finance crisis of 2009 it has turned out to be a lot milder and mostly affects medium-sized companies in the supplier industry.

Five German and five Japanese Top 100 companies were making a loss in 2020 and account for over a half of the 17 suppliers with a negative margin. However, taken as a whole these companies are more like exceptions for Germany and Japan, as a total of 17 German and 27 Japanese automotive suppliers are represented in the Top 100. Germany’s loss-making companies are ZF Friedrichshafen, Continental, Bosch, Mahle and Leoni. The US loss-making companies range from American Axle which leads the loss-making companies with a -8.4 per cent operating income margin, to Goodyear which has a -0.1 per cent operating income margin and is the last on the negative list. Three Japanese companies are nudging zero growth: NTN (-1.1 percent OI), JTEKT (-0.7 per cent OI) and Denso (-0.7 per cent OI). The loss side consists of manufacturers from various fields, from mechanics to electronics.

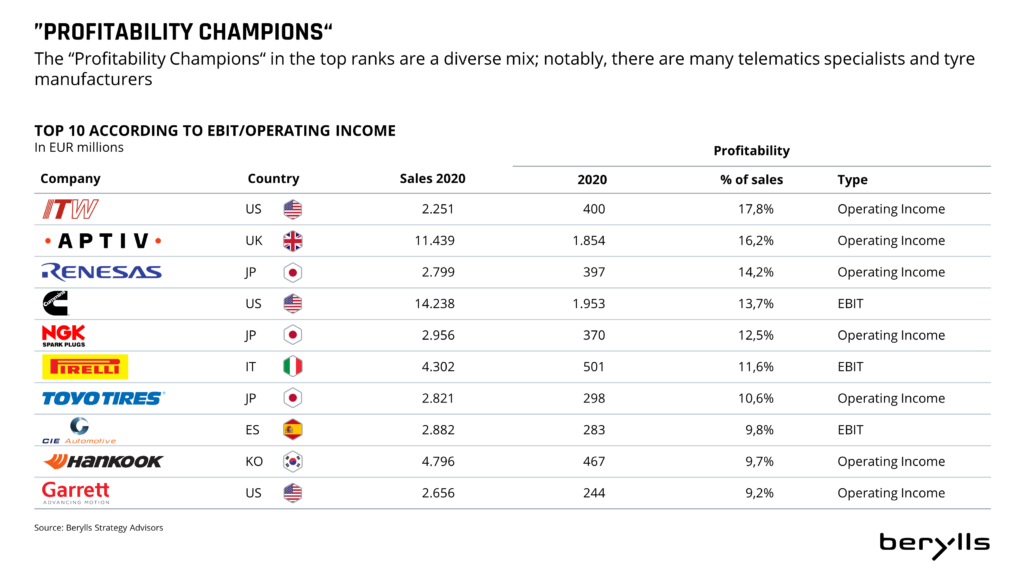

On the other side, this year’s “Profitability Champions“ are also from a very heterogeneous field. The most profitable companies occupying the top ten places are a varied mixture. The top performers come from six different countries and it is mostly telematic specialists and tyre manufacturers realizing positive margins. The top 3 most profitable companies in 2020 are Illinois Tool Works (USA, 17.8 per cent OI), Aptiv (Great Britain, 16.2 per cent OI), and Renesas (Japan, 14.2 per cent OI). The manufacturers with the highest margins were all tyre manufacturers: Pirelli (Italy, 11.6 per cent EBIT), Toyo Tire Corporation (Japan, 10.6 per cent OI), and Hankook Tires (Korea, 10.6 per cent OI). This is despite considerably lower demand in 2020 which had a negative effect on the margins of many other suppliers.

For the sixth year running Bosch is top of the list of the 100 largest automotive suppliers worldwide. The places immediately below Bosch, down to 9th place, go to the same companies as in the previous year. Weichai Power secures 10th place as the first Chinese company in the Top 10, dislodging Valeo (consistently at 10th or 11th place since 2017). This Chinese motor specialist is already well-known as one of the rare sales winners in 2020 and was only at 27th place when the Top 10 list was first published in 2011. Some companies did better than others in the crisis year, and this is largely dependent on geographical location. Suppliers based in Asia and/or with customers in Asia were able to profit from the ability of these countries to regain an attractive economy relatively early. Denso sends Continental down to third place and secures the 2020 silver medal. Magna slides from place four to place five, while ZF profits mainly from the acquisition of Wabco. Also, competitors Michelin and Bridgestone swop positions and now occupy places 8 and 9.

In the past year the effects of the Coronavirus pandemic converged with strong growth in the electromobility sector. Automotive suppliers had falls in sales and production stops to contend with and the majority could not avoid making job cuts. Battery and semiconductor manufacturers remain on a growth path, and so manufacturers such as CATL are increasingly looking for new staff. But European OEMs are dependent on Asian manufacturers such as CATL, Panasonic, BYD or LG Chem. In order to counteract this dependency, Germany will be developed into a European battery centre in the coming years. Various corporations are already working with battery specialists, both on the OEM side and on the supplier side, and throughout Europe Germany is scheduling by far the most projects in the battery manufacturing sector. By 2030 up to 100,000 new jobs will be created in Germany for this sector. German automotive suppliers such as Dräxlmaier, Webasto or Elring, which are already suppliers of battery technology, can also benefit from this.

Suppliers are increasingly adapting their strategies under the keywords electromobility and future technologies. LG is leaving the smartphone business and planning to concentrate on the growth area of components for electro vehicles, networked devices and artificial intelligence. BorgWarner would like to base their growth on acquisitions and at the same time develop more in the electro sector. Infineon’s strategy is to strengthen their core business with semiconductors and the exploitation of new growth markets, and this is what led to the above-mentioned acquisition of Cypress.

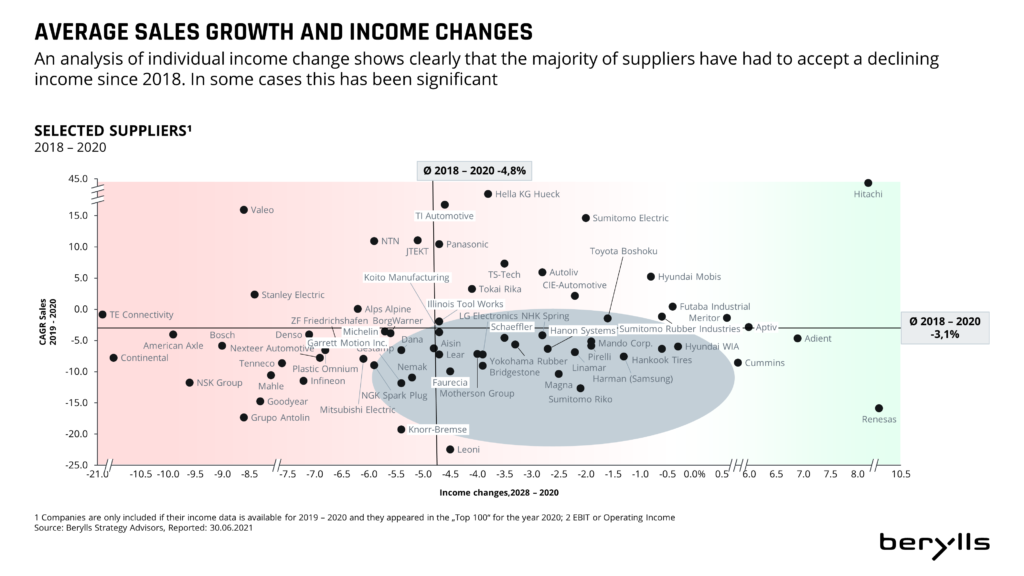

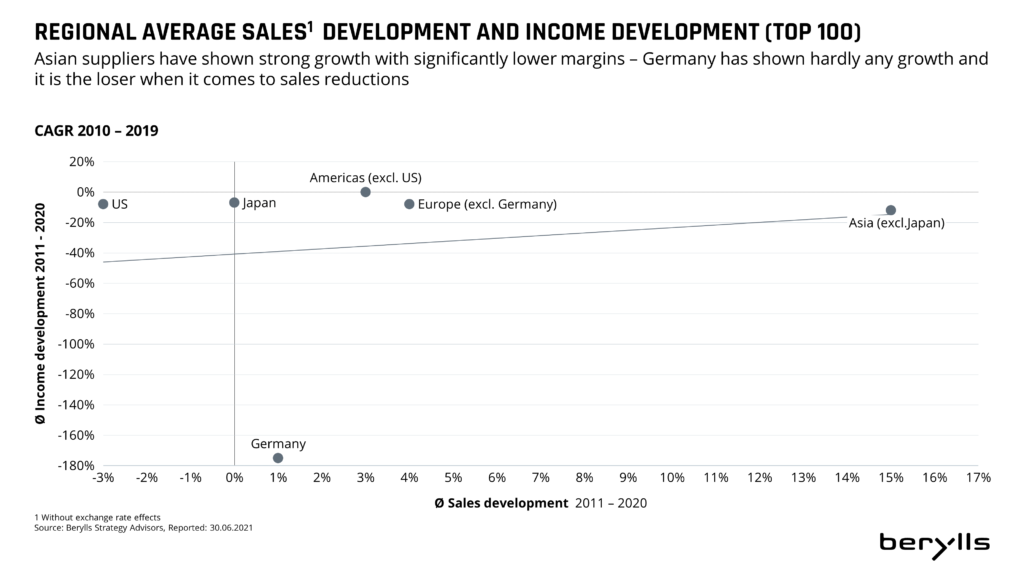

Berylls has been observing the Top 100 worldwide automotive suppliers for ten years. During this time there has been much movement and change both on the markets and on the shop floor. Back in 2011 the industry was on an upswing after the global financial crisis. After that, sales rose year on year, from 2011 onwards (663 billion euros) until 2019 (914 billion euros), by 38 per cent altogether which is a yearly average of 4.1 per cent. And the profitability of the 100 largest suppliers improved every year until 2017, standing at consistently over 7 per cent from 2012 until 2018. In 2020 the total sales of the Top 100 stood at around 800 billion euros – about 20 per cent above the level ten years ago. Profitability, on the other hand, stands at an all-time low of only around 3 per cent – although in 2020 this was largely determined by the pandemic. In 2019, the year before the pandemic, the margin still stood at 6 per cent, a comparable level to 2011 (6.7 per cent). So what has been going on these past ten years?

The geographic distribution of the large suppliers changed in the course of time. There were marked relocations of suppliers from Germany, Japan and the US to Asia. Asian suppliers (apart from Japan) have been forfeiting profitability since 2011 due to their huge sales growth, but have increasingly appeared in the Top 100.

Nine times as many Chinese suppliers made it into the Top 100 in 2020 as in 2011. At that time only Weichai Power was on the list, at 25th place; for 2020 they are ranked 10th, and they now have eight other Chinese companies spread out over the whole of the Top 100 behind them.

The biggest sales winners since 2011 are ZF Friedrichshafen and Tenneco. Bosch took over the top position from Continental in 2015 and has successfully defended this position every year since then. Continental held the top position from 2011 until 2014, slightly ahead of Bosch every year. The Top 100 companies recorded four completely loss-free years between 2013 and 2016.

The best progress within the Top 100 was made by Dräxlmaier (+ 31 places), Grupo Antolin (+ 25 places), and NGK Spark Plug (+ 21 places). The companies who lost the most places were TS Tech (- 41 places), Pirelli (- 31 places) and Meritor (-28 places, after splitting up).

Some companies were seen to come and go during the last decade. Concerns such as Johnson Controls and Honeywell split off their automotive sectors. The suppliers TRW, Delphi Technologies, Calsonic, Behr and Wabco were taken over. Yet more were not able to keep up with the continual sales increases exhibited by the other Top 100 participants and were removed because they were too small, for example IAC, Rheinmetall Automotive and Cooper Standard. The splitting off of parts of companies has also led to new additions over the years. So current occupants of the Top 100 such as Aptiv, Adient, Clarios or Garret Motion have been there for a few years now in the course of their independence. Some suppliers have made it onto the top performers‘ list under their own steam because of strong growth in sales, such as Flex-N-Gate, CATL, Piston Group an the German representatives Aunde, Freudenberg and Infineon.

The coming 10 years will see more marked upheaval. Suppliers with a high proportion of combustion engines like Mahle, BorgWarner, Tenneco or Eberspächer will be pushed to the bottom if they do not take countermeasures. Electric/electronic concerns with strong software skills, like Continental, Bosch or Hella, will grow disproportionately. The Asian concerns, especially the Chinese supplier companies such as the players from IT and entertainment electronics, Huawei, Samsung and LG, will continue to gain importance through acquisitions (also) from traditional companies. The emphasis will shift more strongly in the direction of Asia. However, German suppliers are well equipped to master the next phase of the transformation.

Berylls Strategy Advisors would be happy to support you in this key decision process.

Arthur Kipferler complements the expertise of the Berylls partner team in the fields of market & customer, technologies, sales, and digitalization, as well as in the development and implementation of corporate, product, and regional strategies.

previous years

Vergangene Jahre

igns of a storm brewing - As it was, at the end of 2020, the year 2021 was not looking very promising. Despite a fundamentally positive outlook for the motoring industry, the uncertainties of 2018 and 2019 looked set to continue. Structural change, as well as consumer reticence and vehicle sales stagnation were harbingers of the end of a decade of strong growth.

The year 2019 also showed us that structural change would not proceed quickly – more likely step by step. The merger of Magneti Marelli and Calsonic; Continental’s founding of the company spin-off Vitesco; Tenneco’s takeover of Federal Mogul – all were signs of persistent, continual change for the car industry and its suppliers.

The German M&A market had hardly cooled off at all in 2019, with 293 transactions compared to 295 the previous year. But banks were already viewing credit payments to the car industry with concern, because of the difficult market setting. Despite cheap money and zero-interest policies, an icy wind was blowing around the financing of classical car manufacturers.

New technologies remained risky because of the uncertain market and legal position, as well as the halting monetization and sustainability of business models being trialed. At the same time, the traditional car business seemed to have an ever-closer expiry date. After a long period of growth, pressure for change grew strongly, and there was a push for appropriate investments and strategy changes in the supplier industry.

It took a little while for OEMs and suppliers to accept that they could only reach their targets in CASE technologies through collaboration, because the investments were too enormous for them to be able to manage on their own. But at the same time, political and social problems were destabilizing the market, and rapid change and monetization of new technologies – for example, connectivity services and cybersecurity – failed to emerge.

If we look at profit development in the last few years (-1.5 percent in 2019 compared to 2018, for the biggest 100 suppliers), we can see that there were numerous companies in the lower third of the supply industry which had slipped into the loss zone even before the Covid-19 crisis began in 2020. This alone would be manageable in the short term, but with structural change, the question arises as to whether or not many business models will be sustainable in the future. If old business is wobbling and new business is not yet firmly established, tensions arise and all participants need great skill and dexterity to adopt a clear plan out of the crisis and avoid insolvency.

If we look at the history of how insolvencies develop in the car industry in German-speaking countries, the number since 2010 has involved around 20 (±10) companies a year. However, the global financial crisis of 2008/09 demonstrates that this number can rise sharply in an economic crisis: there were over 80 insolvencies in 2009. Every percentage point of negative development in gross domestic product (GDP) leads to a proliferation in the number of insolvencies. In 2009, the GDPs of major automobile markets fell by between 2 percent and 6 percent (for example, in Germany, Japan, Great Britain and the US), whereas China showed strong growth of around 9 percent.

When it came to vehicle sales in 2009, Great Britain were particularly badly affected, with declines of between 10 percent and 20 percent. Thanks to an environmental bonus, Germany was able to generate a sales surplus of around 20 percent in 2009 compared with 2008, and in this way fended off a deep crisis. However, sales volumes decreased significantly in 2010, to significantly below the pre-crisis level (down 6 percent compared with 2008) and it was not until 2011 that they reached comparable levels again. All these figures are intended to give an idea of the future direction of sales after the Covid-19 economic crisis.

The current situation shows a similar picture for GDP forecasts as for sales. In April the IMF forecast declines of 6 percent for the US, 7 percent for Germany, Great Britain and France, 5 percent for Japan and a rise of 1.2 percent for China. If we line up the numerous crystal balls showing sales forecasts for 2020 and hazard a glimpse into an uncertain future, we will see a corridor reaching from declines of 20 percent to 25 percent for the global car market. There are pessimistic scenarios which paint an even more dismal picture.

Despite support measures for the DACH region – D (Germany), A (Austria) and CH (Switzerland) – Berylls is forecasting a sixfold increase in average insolvency figures for the period March 2020 to mid-2021. Altogether this will probably result in around 120 automobile companies sliding into insolvency. According to Berylls’ forecasts, up to 100,000 jobs will be affected.

Given that the automobile world was a very different one in 2009, after 2020 it will be more difficult to realize a similar story of successful recovery. On the contrary, Covid-19 could accelerate structural change in the German-speaking/European supply industry and even drive insolvencies above 120. The structural damage caused by this insolvency tsunami would be more significant, and the development of new structures would take considerably longer, prolonging the recovery phase. It is also unclear to what extent the banks are prepared to pay out money for the development of new motoring areas after the painful reduction of credit to car suppliers.

The same applies when we look at private equity companies, which can currently find better opportunities for ambitious returns in other industries. Rescue by investors and M&A activities looks difficult; on the one hand, sales prices have risen too high in the last few years while on the other, many financial investors are anxious either not to advance into sectors which they will not be able to sell later, or be unable to handle high expectations of returns. Strategists will proceed very carefully, for the moment preferring to keep hold of their money and wait for better times to make strategic acquisitions.

For takeovers out of insolvency there will be strategists who will have had wish lists for a potential expansion of their own portfolio for quite some time. So the following years could bring further insolvencies, perhaps above the 20 per year mark, and accelerate consolidation. In terms of sales, currently around €12 billion are in play, which come from suppliers who have got into difficulties this year and become insolvent. Reliable forecasts for the actual extent of this will not be calculated until the third and fourth quarter, by which time the number of notable insolvencies can be better quantified and described. We already have some notable examples: Veritas, DGH Druckguss Heidenau and Finoba.

One of the lessons from 2009 should be to avoid a downward spiral of continual pessimistic forecasts. It was such a spiral that tore through the car industry and led to the situation in 2009 in which significantly fewer vehicles were being produced globally than were required on the market. Whereas global demand only reduced by almost three million vehicles, almost nine million fewer were produced than in the previous year. A lack of communication and transparency over highly complicated supply chains made planning more difficult for all concerned, and it was existing vehicles which finally had to fill the trade gap.

If the industry does not manage to make a better job of orchestrating the ramp-up this time, and if participants do not read market opportunities properly, more damage could be done than in 2009. We must avoid a situation where capital is gained from the financial stress suffered by normally solid companies. In the medium term this would be alleviated if transformation was actually abandoned altogether. This is the reason why people are increasingly calling for structures to be created in which companies in trouble can find a safe harbor (e.g. takeovers using a fund created by banks, investors or unions). However, OEMs have an interest in keeping their highly complex supply chains stable and carrying out the supplier transformation in coordinated channels. It is not known whether “problem companies” might also land in this safe harbor – companies which would have been better wound up – otherwise the pace of this wise change in the industry will be slowed down.

The market will be reassessed, and it must be steered with measured judgement and supported at the right point. Alongside investments for CASE, other investments are needed to rebuild the supply chain, ranked in a similar way. The top priority at the moment is to secure liquidity, especially as many car suppliers in the supply chain are system-relevant. This alone is a mammoth task for the industry, and it is not enough on its own. New ideas are needed, for example the transparency mentioned earlier, to steer the ramp-up on the basis of demand.

In addition to all this, a mixture of purchase incentives to support the industry, including sustainability and environmental demands, needs to be provided through hybrids, battery electric vehicles (BEVs) or fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs). However, structural problems should not be concealed, and short-term purchase incentives should not again lead to medium-term over-capacity and an incorrect vehicle portfolio that runs contrary to long-term climate goals.

When it comes to rescue funds for suppliers, we should proceed with clear criteria for system relevance, continuation of structural change and a clear central control body, compatible with the market reassessment of “zombie firms.”

The setting of these parameters will define whether or not we will see an even higher number of insolvencies. There should be opportunities for all participants (including suppliers, banks, private equity firms, OEMs and politicians) to continue the change which has been set in motion, to transform the car industry. Powerful waves seem unavoidable, but they must be prevented from getting bigger and forming a tsunami.

Dr. Jan Dannenberg (1962) has been a consultant for the automotive industry since 1990 and became a founding partner of Berylls Strategy Advisors in May 2011. Until spring 2011, he worked with Mercer Management Consulting and Oliver Wyman in Munich, Germany, on international projects – for five years as Associate Partner, and another three years as Partner. He is a recognized specialist in innovation and brand management in the automotive industry, and primarily advises suppliers and investors on strategy, M&A and performance improvement. In addition he is Managing Director at Berylls Equity Partners, an investment company that specializes on mobility enterprises.

Bachelor of Arts in economics at Stanford University, USA; business administration and doctorate degree at the University of Bamberg, Germany.

previous years

Vergangene Jahre

ovid-19: A unique situation - Never before has a global crisis hit the automobile industry with such speed and impact.

Within just a few weeks, large areas of car production had come to a standstill, with serious results: break-up of supply chains, announcement of short-time working, temporary factory closures and laying-off of temporary staff. Rapid expenditure control coupled with protection for employees’ health were the first steps taken by every supplier. Now, after three months’ experience of the coronavirus crisis, factories can start up again and companies face the challenge of finding the right way to carry out the ramp-up and forecast demand.

It is obvious to nearly every supplier that coronavirus will mark a turning point for their company. Even before the pandemic lockdown, firms were having to put the brakes on spending. The OEMs’ wave of cost savings, for example Daimler with €1.5 billion (November 2019), BMW with €12 billion up to the year 2022 (March 2020) by means of “Performance Next”, and the VW brand with €15 billion in savings planned up to the year 2023 (March 2019), were combined with demands that suppliers reduce their prices again.

In the current climate, familiar measures are being taken, such as adaptation of capacity in the manufacturing process, selective redundancies, optimization of working capital, and easing of terms with outside creditors. The hope is that there will be a rapid and marked recovery. There is nothing wrong with this per se, and in the past these restructuring projects and slim, efficiency-oriented business models have guaranteed companies’ survival and success again and again. But the risks are priced in, and they will rise significantly after the immediate Covid-19 crisis passes.

CASE investments must continue to be made, in order to keep up with the transformation of the supplier industry – the amortization of these expenses is being delayed and that makes the position even more insecure. The future development of the automobile industry, especially with regard to production runs and vehicle classes, segments and power units, is unpredictable. The catchword for this is VUCA: Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, Ambiguity. Safeguarding of the supply chain for JIT/JIS delivery is hardly possible while some factories might be suddenly standing empty and others do not manage the ramp-up or restart their output.

The result is that an operations and performance crisis can rapidly turn into a financial and liquidity crisis. Then shareholders, creditors and banks will expect more than the usual improvements. In any case these will be nowhere near enough, because adaptations and restructuring requirements will be more substantial, more fundamental and more profound in the coming two years than they have been in the last 30. Every car supplier must be prepared to accept significant restructuring measures.

The right ingredients for success in an intelligent restructuring are decisive. First, there needs to be process reliability: the restructuring must be carried out in a sustainable and pragmatic way. Above all it is crucial to find a holistic solution which coordinates all the control levers and quickly identifies and reacts to the causes of the crisis.

Secondly, restructuring expertise is needed: alongside the company’s own internal team it is essential to have access to external restructuring expertise. Experience, knowledge and networking skills among all company roles are essentials too. Moreover, if the restructurer can keep a certain emotional distance this can save the company culture from damage.

Thirdly, automobile know-how is important: as well as knowing about the car industry, it is important to know how to make improvements. Benchmarks from the sector’s best players in matters of costs, earning power, financial structure and so on, help to quickly identify the right savings opportunities or structures. Finally, there needs to be stakeholder insight: anything which is important for a bank should never be unimportant to the OEM. And it is precisely when there is a crisis that the car supplier must be fair to everyone.

Berylls has identified nearly 30 control levers from six categories which need to be investigated in the context of intelligent restructuring programs – and used if there are any problems – in order to tackle the company crisis quickly and specifically, and solve it. It is not enough to simply reduce costs. Every company crisis is unique. Whereas for one supplier it might be mainly the financial and debt structure that is problematic, for another it could be the situation with the client that is the main cause.

On the one hand, identification of the cause of the crisis should be carried out alongside the dimensions of strategy, governance, operations, overheads, financing and transparency. On the other hand, crisis management should guarantee that a coordinated and holistic solution works for each individual control lever. Liquidity crises must be handled with a different dynamic, and often in a more pragmatic way, than a strategy crisis. This requires not only substantial experience in the process of crisis management and restructuring, but also sound knowledge about which solutions are sustainable specifically for the car industry. Anyone tackling restructuring in this intelligent, holistic way will emerge from the crisis in a stronger position.

Dr. Jan Dannenberg (1962) has been a consultant for the automotive industry since 1990 and became a founding partner of Berylls Strategy Advisors in May 2011. Until spring 2011, he worked with Mercer Management Consulting and Oliver Wyman in Munich, Germany, on international projects – for five years as Associate Partner, and another three years as Partner. He is a recognized specialist in innovation and brand management in the automotive industry, and primarily advises suppliers and investors on strategy, M&A and performance improvement. In addition he is Managing Director at Berylls Equity Partners, an investment company that specializes on mobility enterprises.

Bachelor of Arts in economics at Stanford University, USA; business administration and doctorate degree at the University of Bamberg, Germany.