he Chinese government has backed EV development for two decades, but the number of ICE cars on the roads will still be increasing in 2030

By every measure, China is the world’s most important car market – this year 29 million vehicles are expected to be sold in the country, compared with 21 million in the US and 20 million in the EU. China will further eclipse these two regions in the coming decade: by 2030, Berylls expects 38 million new vehicles to be registered annually in China, equivalent to 31% of the global market, compared with 20% and 18% market share in the EU and US respectively.

The country is also the world’s biggest xEV market, with around 3 million of what the Chinese government calls ‘new energy vehicles’ (NEVs) sold in 2021. Will it retain this leading position over the next decade, as European and US carbon emissions commitments drive the xEV transition in those regions?

NEW ENERGY VEHICLES SOLD (in 2021)

At the UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow in 2021, China committed to the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement to limit global warming by 1.5 °C, and the country (the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitter) has set a goal of being carbon neutral by 2060. Around 10% of China’s emissions come from the transport sector, and one of the key milestones en route to 2060 is the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s target for NEVs to account for 40% of all new vehicle sales by 2030.

In this report, we will look at China’s plans for decarbonizing road transport and how realistic its goal is, in light of the following market dynamics:

China will be the biggest xEV producer worldwide, making 13 million battery electric vehicles (BEVs) a year by 2029

The country will more than triple its battery cell production capacity by 2030

Customer sentiment seems to have fully embraced electrification, and Chinese OEMs such as NIO are ranked more highly than international brands

However, the number of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles sold will still be rising in 2030, and make up the largest proportion of cars on China’s roads

China has had a systematic NEV strategy for decades: the target of reaching 40% of new vehicle sales from NEVs by 2030 is not a hurried concession to the growing international pressure to address climate change. Even before the turn of the millennium, the country had a goal to become the world’s leading automotive nation, and new electric drivetrains were a potential route to overtaking established leading markets such as Germany and the US.

NEV development was first funded in the CCP’s tenth Five-Year Plan in 2001, and up to 2008 the focus was on developing pilot vehicles with electric drivetrains. From 2009 to 2016, NEVs were sold to the local market with significant government subsidies and purchase incentives.

Since 2017, subsidies have been much more strictly linked to technical specifications such as range. The current funding program will finish at the end of 2022, however, as has happened in the past, subsidies may be extended, with stricter requirements for eligible EVs. The NEV market is also supported by the “dual credit policy”, a form of carbon market, where OEMs have to meet quotas for NEV production (16% in 2022).

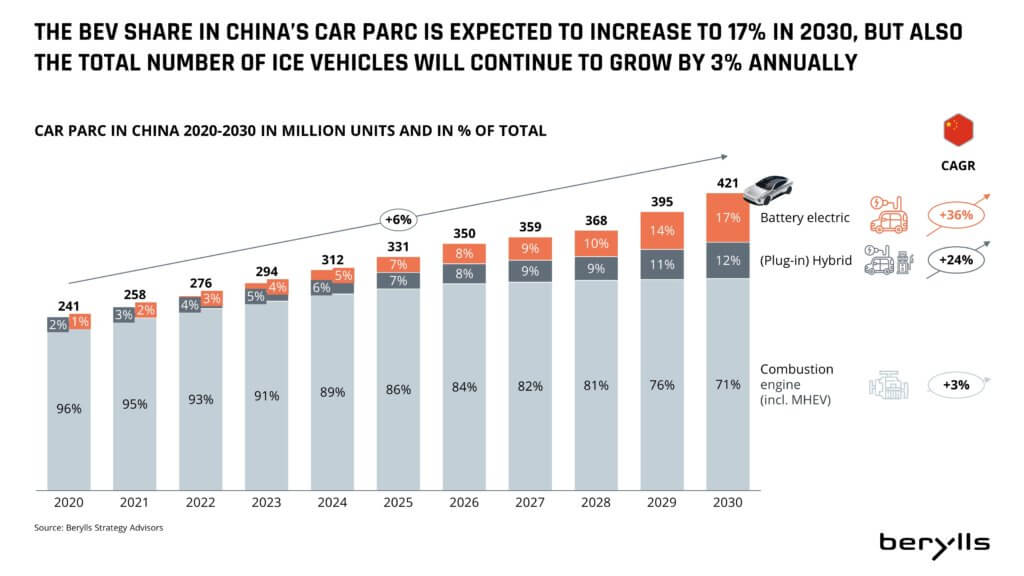

However, despite two decades of government support for e-mobility as a means to close the gap between Chinese and foreign OEMs, our analysis shows that the total number of ICE vehicles on the road in China will continue to increase by 3% a year out to 2030, even if the target quota of 40% NEVs is reached.

As the chart below shows, traditional drivetrains (including mild hybrid vehicles) will account for 71% of cars on the road, the equivalent of 300 million vehicles, at the end of the decade. China’s current NEV targets therefore do not go far enough to cut the number of carbon-emitting vehicles on the road.

Figure 1

While the task of cutting the number of polluting vehicles on the road is far from complete, in several key areas China’s long-term NEV strategy has put it far ahead of Europe and the US.

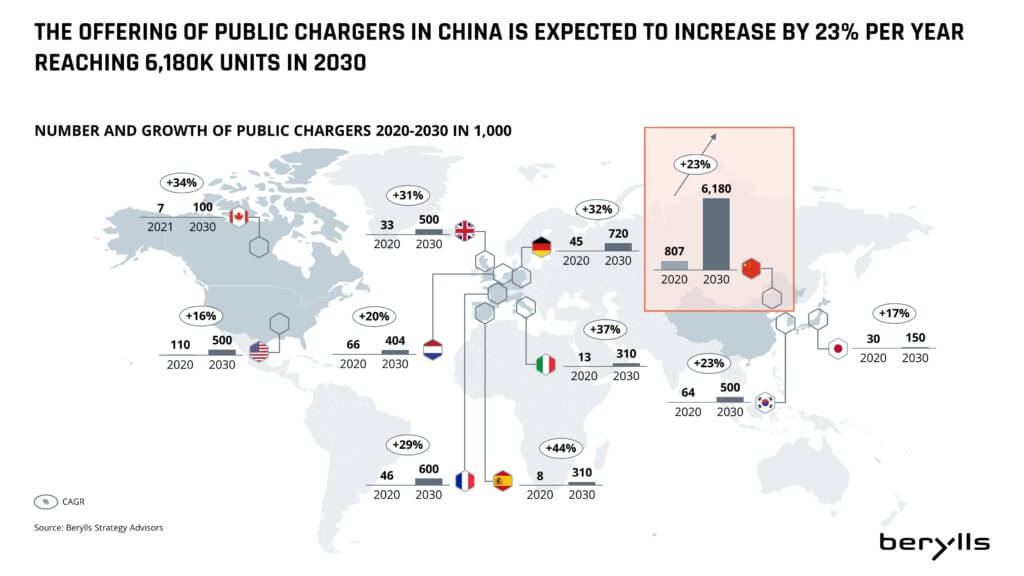

The CCP recognized early on, for example, that the success of NEVs would depend heavily on the availability of charging points. Government programs have subsidized the building of public charging stations since 2014, and approximately 1 million have now been installed.

This means China has by far the largest network of EV charging infrastructure worldwide, with a ratio of 8 BEVs to one charging station. That compares with a ratio of 20:1 in the EU, and sets the global benchmark. Progress is not stopping – as Figure 2 shows, the number of public charging points is expected to increase by 23% a year to reach 6.18 million by 2030.

Figure 2

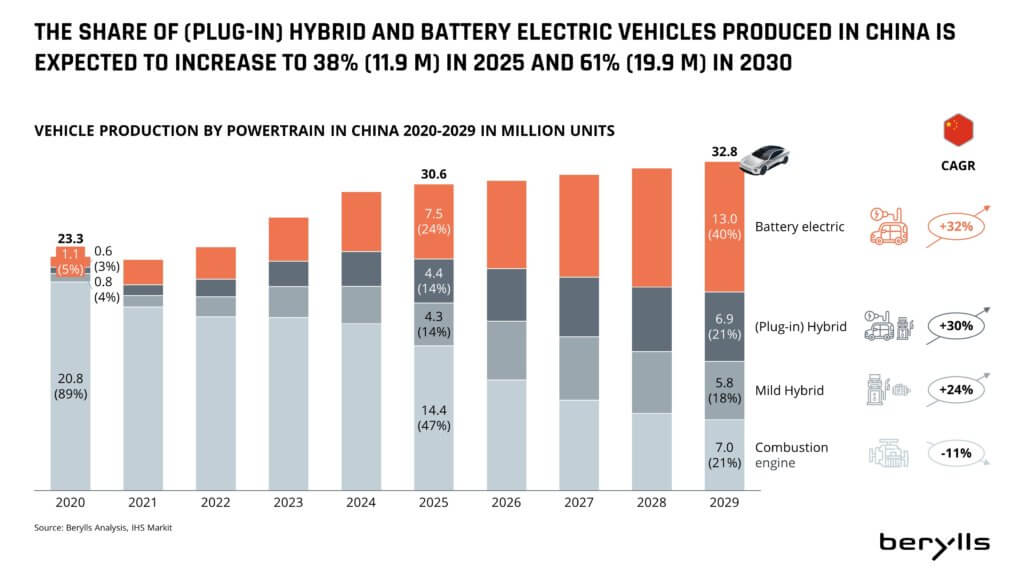

BEV production is also ramping up – today the segment accounts for around 5% of vehicle production, and plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) for another 3%. However, we expect BEV production to accelerate significantly, growing by 32% a year to reach 13 million vehicles annually in 2029 – the equivalent of 40% of all car production (Figure 3). By comparison, we expect the US to produce 4 million BEVs a year in 2029, or 36% of total production volume.

Figure 4

China’s long-term strategy for NEVs also means it has built up a world-leading advantage, in the critical area of battery supply.

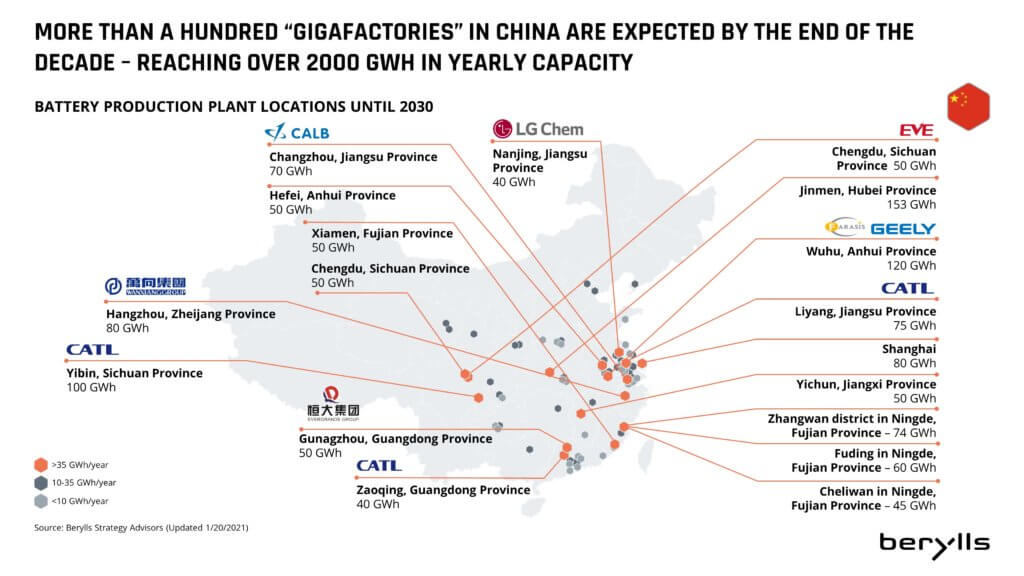

At present, about 80% of the world’s EV batteries are made in China, and OEMs worldwide are heavily dependent on exports from the country: around 70 percent of the battery cells needed for cars manufactured in Europe, for example, come from China. China’s CATL is now the global market leader in lithium-ion EV batteries, along with LG Energy Solution (South Korea) and Panasonic (Japan).

Today’s installed production capacity in China is about 650 GWh/year; we expect capacity to increase more than three-fold to 2,260 GWh by 2030, equivalent to a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 16.5%.

Assuming an average capacity of 90 kWh (BEV) / 15 kWh (PHEV), we expect domestic demand in 2029 to be around 1,300 GWh a year, so China will still have plenty of capacity to export battery cells.

Highlighting the scale of China’s battery cell production advantage in comparison with other large automotive markets, there are already several dozen “gigafactories” for Li-ion cells in the country, whereas in the US there are just five. By the end of this decade, there will be more than 100 gigafactories in China, while in the US, 17 have been announced (Figure 5).

Local production of battery cells is a key advantage for Chinese OEMs, and a vital enabling factor in making the country a leading automotive nation. A key question in the years ahead is whether the country can maintain its pioneering role, not only in terms of quantity, but also in terms of battery technology.

Figure 4

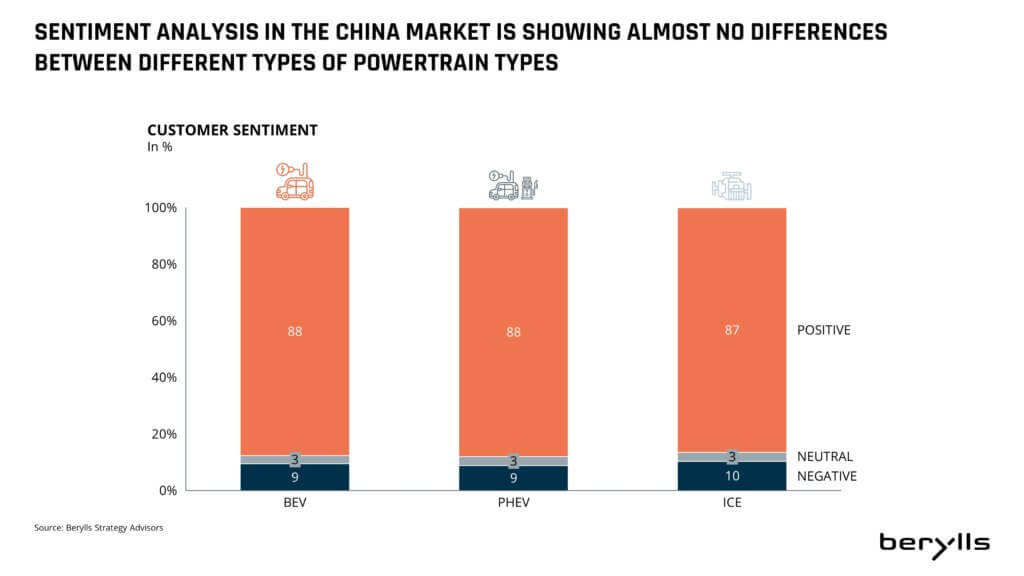

Customers in China seem to have fully embraced electrification. Our analysis of customer sentiment in the country showed almost no differences between the various powertrain types (Figure 6). In fact, the differences between their positive or negative feelings about individual models are significantly greater than between BEV, PHEV or ICE groups.

Figure 5

Reasons for this include the fact that a high proportion of driving happens in urban areas in China (compared to the US for example) and BEVs and PHEVs have a clear advantage in that environment. Other advantages are being able to drive NEVs on days when ICE vehicles are banned due to high pollution levels, and government subsidies for NEVs. An appealing range of NEVs in the lower price segments made by Chinese OEMs also firmly established BEVs and (P)HEVs in the Chinese volume market at an early stage.

Figure 6

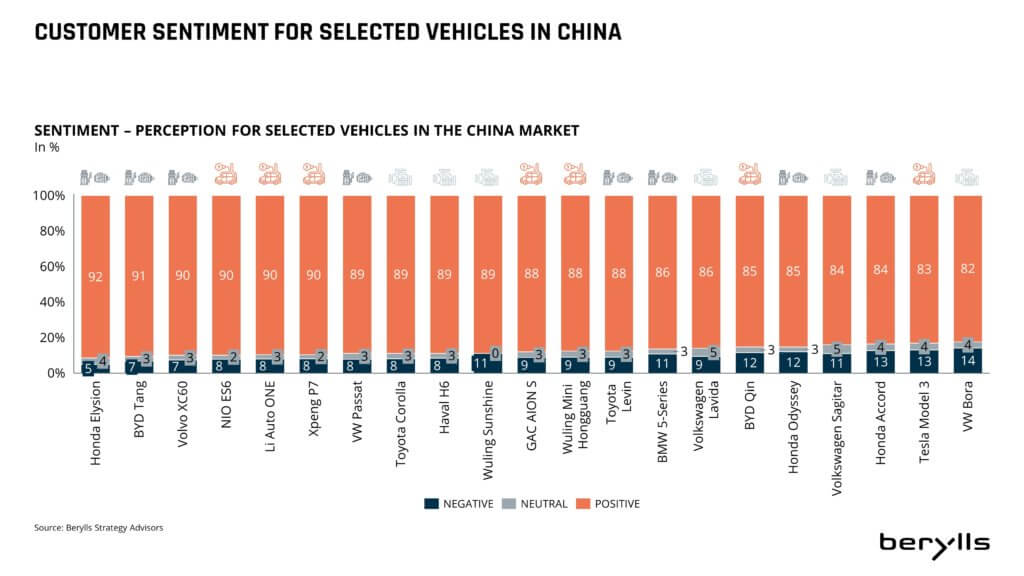

Chinese OEMs also know their customers: the NIO ES 6 performs significantly better in customer sentiment scores than a Tesla Model 3, for example, and a BYD Tang PHEV ranks significantly higher than a BMW 5 Series PHEV (Figure 7).

Driving performance and technical details are not as relevant to NEV customers in China as in other markets, whereas cars with a modern aesthetic and a spacious interior win positive ratings.

The driving range of NEVs has a big impact when it comes to negative sentiment, particularly any difference between real daily range and available range as displayed in the vehicle. Range anxiety is still an important issue for China’s NEV customers, but for different reasons than in the US and Europe – in regions with very high or very low temperatures, heating or cooling can lower the range significantly, and being stuck in traffic also significantly drains the car’s battery. However, the growing number of charging stations in China means drivers are less concerned about being unable to charge when they need to, or during a long journey.

China has vital first-mover advantages in battery cell production and NEV charging infrastructure, as well as NEV production. Customers accept EV engine technology and Chinese OEMs are well liked. Yet if China is serious about decarbonizing road transport, it must go further to ensure the number of carbon-emitting ICE vehicles on the roads are reduced. Currently, there will be 300 million of them on the road in 2030, compared with 257 million this year.

Extending the subsidies due to expire at the end of 2022 would encourage greater NEV adoption, although we would expect the government to make future subsidies smaller and add more requirements for the NEVs they apply to. A more intensive dual credit policy for OEMs, with higher quotas for NEV production, would also drive the market forward.

Dr. Jan Burgard (1973) is CEO of Berylls Group, an international group of companies providing professional services to the automotive industry.

His responsibilities include accelerating the transformation of luxury and premium OEMs, with a particular focus on digitalization, big data, connectivity and artificial intelligence. Dr. Jan Burgard is also responsible for the implementation of digital products at Berylls and is a proven expert for the Chinese market. Dr. Jan Burgard started his career at the investment bank MAN GROUP in New York. He developed a passion for the automotive industry during stopovers at an American consultancy and as manager at a German premium manufacturer.

In October 2011, he became a founding partners of Berylls Strategy Advisors. The top management consultancy was the origin of today’s Group and continues to be the professional nucleus of the Group. After studying business administration and economics, he earned his doctorate with a thesis on virtual product development in the automotive industry.